There are a variety of methods used to estimate the present rate of mass loss from the Greenland ice sheet, including satellite altimetry, satellite gravimetry and input-output assessments. All of these methods generally agree that since 2005 the ice sheet has been losing c. 250 Gt/yr of mass (equivalent to 8000 tonnes of ice per second). Partitioning this mass loss into climatic surface balance (i.e. snowfall minus runoff) and ice dynamic (i.e. iceberg calving) contributions is a little more challenging. Partitioning recent mass loss into surface balance or ice dynamic components requires us to look at the changes in each of these terms since a period during which the ice sheet was approximately in equilibrium. Conventionally, the ice sheet is assumed to have been in equilibrium during the 1961-1990 so-called “reference period”.1

The three main methods of measuring present-day ice sheet mass balance: (1) snowfall input minus iceberg output, (2) changes in elevation using satellite altimetry, and (3) changes in gravity using satellite gravimetry (from Alison et al., 2014)5.

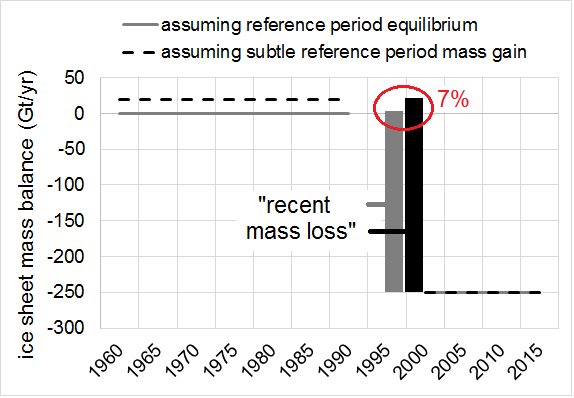

Our recently published study in the Annals of Glaciology takes a hard look at the mass balance of the high elevation interior of the Greenland ice sheet during the reference period2. We difference the ice flowing out of a high elevation perimeter from the snow falling within it, and conclude that the ice sheet was likely gaining at least 20 Gt/yr of mass during the reference period. This implies that rather than ice sheet mass balance decreasing from c. 0 Gt/yr (or “equilibrium”) during reference period to c. -250 Gt/yr since 2005, it may have actually decreased from c. +20 Gt/yr of subtle mass gain during reference period to c. -250 Gt/yr since 2005. This interpretation would mean the “recent” (pre-1990 to post-2005) mass loss of the ice sheet is actually 7 % greater than might conventionally be assumed (270 vs. 250 Gt/yr). Seven percent more recent mass loss than conventionally assumed might not sound like much, but it becomes important when we try to partition mass loss in surface balance or ice dynamics components.

Illustration of how a subtle mass gain during reference period (1961-1990) , when the Greenland ice sheet is conventionally assumed to have been in approximate equilibrium, can influence the magnitude of “recent mass loss” used to partition surface balance and ice dynamics components of mass loss.

We also assessed whether surface balance or ice dynamics were responsible for subtle reference period mass gain. We concluded it was more likely long term ice dynamics, resulting from the downward advection through the ice sheet of the transition between relatively soft Wisconsin ice (deposited > 10.8 KaBP) and relatively hard Holocene ice (deposited < 10.8 KaBP). In 1985, Niels Reeh proposed that subtly increasing effective ice viscosity was resulting in cm-scale ice sheet thickening3. Increased iceberg calving, or enhanced ice dynamics, are conventionally assumed to be responsible for c. 100 Gt/yr of recent mass loss4. Since we conclude ice dynamics were likely responsible for subtle reference period mass gain, we are implying that mass loss due to ice dynamics may actually be c. 20 Gt/yr greater than conventionally assumed, or c. 120 Gt/yr rather than c. 100 Gt/yr since 2005. Without invoking any departures from the conventional view of changes in surface balance since reference period, this infers 20 % more mass loss due to ice dynamics since reference period. This becomes important if diagnostic ice sheet model simulations are calibrated to underestimated recent ice dynamic mass loss, which may subsequently bias prognostic model simulations to similarly underestimate future ice dynamic mass loss.

An ice sheet composed of relatively hard Holocene ice is theoretically c. 15 % thicker than one composed of relative soft Wisconsin ice. Today’s ongoing transition from Wisconsin to Holocene ice within the Greenland ice sheet should theoretically result in cm-scale transient thickening (after Reeh, 1985).

Pondering how a millennial-scale shift in ice dynamics may be responsible for subtle mass gain during the 1961-1990 period, and how that ultimately influences our understanding of present-day mass loss partition, is definitely a rather nuanced topic. I am guessing there are not many non-scientists still reading at this point. Spread over the high elevation ice sheet interior, a 20 Gt/yr mass gain is equivalent to a thickening rate of just 2 cm/yr, which is within the uncertainty of virtually all mass balance observation methods, including in situ point measurements. I suppose the thrust of our study is to be receptive to the idea that millennial scale ice dynamics may be contributing to a subtle ice sheet thickening that underlies both past and present ice sheet mass balance, and to appreciate the non-trivial uncertainty in partitioning recent mass loss into surface balance and ice dynamic components that stems from the particular reference period mass balance assumption that is invoked.

1Van den Broeke, M., J. Bamber, J. Ettema, E. Rignot, E. Schrama, W. van de Berg, E. van Meijgaard, I. Velicogna and B. Wouters. 2009. Partitioning Recent Greenland Mass Loss. Science. 326: 984-986.

3Reeh, N. 1985. Was the Greenland ice sheet thinner in the late Wisconsinan than now?

Nature. 317: 797-799.

4Enderlin, E., I. Howat, S. Jeong, M. Noh, J. van Angelen and M. van den Broeke. 2014. An improved mass budget for the Greenland ice sheet. Geophysical Research Letters. 41: doi:10.1002/2013GL059010.

5Alison, I., W. Colgan, M. King and F. Paul. 2014. Ice Sheets, Glaciers, and Sea Level Rise. Snow and Ice-Related Hazards, Risks and Disasters. W. Haeberli and C. Whiteman. Elsevier. 713-747.