Charter aircraft are now ubiquitous in Greenland ice sheet research, but it wasn’t always that way. Overland traverses of specialized low-ground-pressure vehicles were the standard ice-sheet science platform until the early 1970s. The subsequent aircraft-era was born by the shifting nature of ice-sheet expeditions. Most expeditions are no longer months of diverse basic measurements, but rather weeks of highly-focused measurements. Small aircraft, like the ski-equipped Twin Otter in particular, have allowed ice-sheet expeditions to dart into any corner of Greenland with far more convenience than the lumbering ground vehicles used by larger traverse parties.

Figure 1 – Left: Specialized ground traverse vehicle used by the French Polar Expedition in 1959. Right: Charter Twin Otter aircraft used by University of Colorado expedition in 2008.

Back in 2008, the US National Science Foundation signaled that the economics of large-scale Greenland ice sheet logistics were shifting, when it initiated the quasi-bi-annual Greenland Inland Traverse from Thule Air Base to Summit1,2. The round-trip 70-day traverses use modified farm vehicles. Each traverse phases out more than 100 tonnes of Summit Station re-supply that was previously performed by ski-equipped C-130 Hercules aircraft.

If you spend an inordinate amount of time looking at the logistics for ice-sheet expeditions, it might seem like ground vehicles are now starting to edge into the realm of financial possibility for compact expeditions as well. Especially since the last Greenland-based Twin Otter was transferred out-of-country c. 2012, forcing ice-sheet researchers to ferry Twin Otters from Canada or Iceland on an as-needed basis.

Imagine a hypothetical expedition of six researchers for two weeks to survey a 100 km transect in the middle of South Greenland. My guess is that it would take around USD 127,000 to get in and out with a chartered Twin Otter. If the same expedition took an extra week to commute using two specialized ground traverse vehicles, my guess is that it would take around USD 203,000 (Table 1). If you relocate to North Greenland, and assume 50% more flight burden, the charter aircraft option increases to USD 179,000, while the cost of traversing from the nearest suitable settlement effectively remains the same.

Table 1 – Estimated expenses of transportation logistics associated with two-week charter aircraft and three-week specialized ground traverse vehicle expeditions (in USD). The charter aircraft scenario assumes deploying four ancillary snowmobiles and the ground traverse assumes two specialized vehicles.

I think this is a fair zero-order analysis. USD 250,000 buys a pretty specialized traverse vehicle, and assuming a minimum of 105 days of use (five 21-day seasons) is on the aggressive end of amortization scenarios. Sure, there are indirect costs associated with owning a traverse vehicle, like shipping it to/from Greenland, but these are small in comparison to the capital cost. The reality of expedition logistics is that large unexpected costs can drown planned costs: an aircraft recalled to its home-base or a broken drive-train can ring up USD 40,000 overnight.

If the economic advantage of charter aircraft over traverse vehicles is within 12% in North Greenland, perhaps it is worth looking to look at another metric: carbon. Ice-sheet researchers generally fall into the “climate aware” crowd; the consequences of anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions motivate much of our climate change research niche. The Paris Agreement alone provides a strong motivation to understand the climate impacts of our climate change research activities.

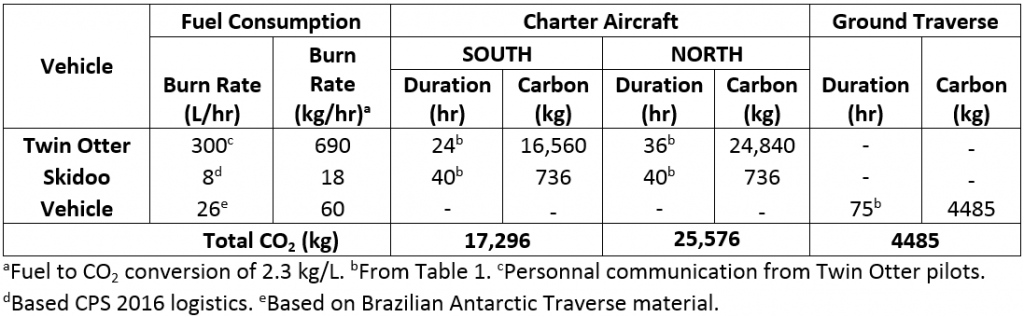

Table 2 – Estimated direct carbon emissions associated with ice-sheet expeditions under the logistical support scenarios of a single charter aircraft versus two specialized ground traverse vehicles (Table 1). This does not include non-trivial indirect emissions.

Perhaps it is no surprise that the slow-and-steady ground traverse scenario has a smaller direct carbon footprint than the fast-and-convenient aircraft scenarios. But what may be surprising, is just how much smaller: four to six times less carbon dioxide emitted! Now, this is just the direct carbon footprint, the carbon dioxide associated with burning fueling during expedition activities, and does not include the non-trivial indirect emissions associated with aircraft or vehicle manufacture. Full life cycle carbon accounting is a huge issue: an aircraft can easily have a 100x more working days in its life than a specialized ground vehicle.

So, why even spend time on rough estimates of the cost and carbon associated with ice-sheet logistics? Well, earlier this month, the US National Science Foundation issued a “Request for Information on Mid-scale Research Infrastructure”. The NSF asks for this type of input once in a literal blue moon to develop multi-year strategy to address the big-picture infrastructure needs of the science and engineering community. Not just the cryospheric community, but the entire research community. These sorts of calls are the time for researchers to team-up and simply ask for the chance to ask for big-ticket items, things that cannot be financed through smaller individual grants.

Figure 2 – Sampling of contemporary ice-sheet vehicles (Left to Right): Custom Toyota Land Cruiser, Hagglunds Arctic Tracks, Tucker Sno Cat, and Arctic Truck Toyota Hilux.

Researchers teaming up is critical to chasing the widespread adoption of lower-carbon ground traverses; the finances only make sense at group-scale. Higher-carbon charter aircraft still provide cheaper one-time ice-sheet access than lower-carbon ground vehicles. Even if a single research project can afford the cost of one or two amortized ground traverse expeditions, virtually no research group has sufficiently committed funding to fully amortize vehicle purchases over 5+ expeditions. This seems to be a clear and present opportunity for a research consortium to own Greenland traverse vehicles and lease them to individual science teams.

This is not a new idea among folks who organize Greenland ice sheet expeditions. But, perhaps it is time for us to organize the kind of bona fide “evidence of research community support” that any funding agency wants to see before supporting a transformative infrastructure shift. So, if you are into ice-sheet research and interested in exploring the possibility of shared ice-sheet traverse vehicles in Greenland, then I have started an email listserve to connect and exchange ideas on this rather quirky topic. Otherwise, if you are just taking a moment to peer into the void of ice-sheet logistics, I hope you can slightly better appreciate the practicalities of exploring lower-carbon solutions to ice-sheet transportation!

Anyone interested in hashing out the logistics of shared traverse vehicles for #Greenland ice sheet science? See: https://t.co/alkeEB9d19 pic.twitter.com/0D9G2tRxdi

— William Colgan (@GlacierBytes) November 2, 2017